(a) Loss of the Victoria Cross

After Samuel’s discharge from the Navy at Portsmouth, England, in May 1865 it is said he visited Commander Hay’s mother and she gave him a silver plated revolver as a gift for attempting to save Commander Hay’s life at Gate Pa. Whether or not he visited his family in his birthplace is not known.

How and when Samuel returned to New Zealand is unknown. It seems he sailed from England to Sydney (because he lost his seachest in Sydney) and then on to New Zealand but on what ship(s) is again unknown. From Sydney it appears he wanted to visit New Zealand and at this time (1865-1866) the west coast of the South Island of New Zealand was experiencing a gold rush and he may have come to try his luck as a goldminer. Evidence to support this theory is found in his Notice of Intention to Marry dated 16 May 1870 in which he gave his occupation as a miner.In the same Notice he gave his time in New Zealand as 18 months which would place his arrival in New Zealand (if indeed he came direct from Sydney) at approximately September-October 1868.

With regard to the loss of the Victoria Cross there are 2 stories as to how it came to be lost.The first is that he had left his seachest containing the Cross in a boardinghouse in Sydney when the Harrier returned to England in 1864. The second is that he returned to England in Harrier with the sea chest and returned with it to Sydney before leaving it there when he visited New Zealand. My own preference is for the second theory.

When Samuel decided to visit New Zealand from Sydney he had left his seachest containing the Victoria Cross, the revolver from Commander Hay’s family, a drinking flask, a watch and chain and photographs with a family called Goodman who ran a boardinghouse in Sydney where he had been staying.

When he decided to settle in New Zealand he sent for his sea chest but received no reply. He put the matter in the hands of the police and was told by them that the Goodman’s had returned to England. He never saw the seachest again and no more was heard of the Victoria Cross until 1909 and a number of years after his death.

On 21 May 1870 Samuel married Agnes Ross in the Registrar’s Office at Ross. Agnes came from Elgin in Scotland and apparently had arrived in New Zealand with her mother,stepfather and brother Andrew who had also served in the Royal Navy. They landed at Gillespies Beach which was also on the the South Island’s west coast and also experiencing a gold rush. In the Notice of Intention to Marry of 16 May 1870 she gave her occupation as a spinster and her time in New Zealand as 12 months which would place her arrival at approximately April-May 1869. As with Samuel by what ship(s) she and her relations travelled from Scotland to Australia/New Zealand is unknown.

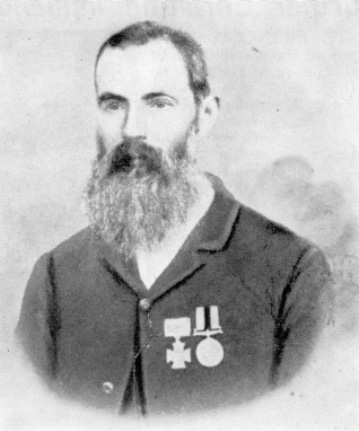

(b) New Zealand Medal

In 1885 Samuel was granted the New Zealand medal for his service in the New Zealand Wars. This medal was sanctioned on 1 March 1869 to be issued to survivors only of those who had taken part in the New Zealand Wars between 1846 – 1847 and 1860 -1866 and who were alive on 1 March 1869.. With Royal Navy personnel the medal was generally issued only to those crew who had landed and been engaged with the enemy. The medals were generally dated with the period of service in New Zealand and medals for the 1863-64 period of service were awarded to 79 crew from the Harrier.

(c) Military Grievances

An issue in which Samuel was involved was the settlement of grievances by former British soldiers and seamen who had settled in New Zealand and compensation they sought from the New Zealand government.

The background to the issue was that in 1858 the Auckland Provincial Government (New Zealand provinces had their own system of government until 1876 when it was abolished) passed a law intended to encourage the settlement of military settlers in the Auckland province. This law provided for free land to such settlers who retired from the British forces intending to settle in Auckland and who made a claim within a certain time. Later in 1858 the New Zealand government extended the law to the provinces of Wellington and New Plymouth. Claims had to be filed by 1859.

The system officially ended by 1860 but it appears that, word having spread amongst British forces serving around the world, many ex-servicemen came to settle in New Zealand expecting a grant of free land and finding that didn’t happen. A number of petitions were presented to the New Zealand Parliament and on 9 July 1889 the Parliament appointed a committee to report on the petitions. In its report back to the Parliament the Committee recommended that power be given to the Chief Commissioner of each land district to decide upon the merits of each claim. This recommendation was given effect by Parliament passing the Naval and Military Settlers’ and Volunteers Land Act 1889 in September 1889 which set out a number of categories for making a claim.

Claimants were to send in their claims setting out their military service and their reason for settling in New Zealand by 31 December 1890. Samuel was such a claimant under the category of “All persons who retired from Her Majesty’s Naval or Military Service with a good character for the purpose of settling in New Zealand, at any time before the thirty-first day of December, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-eight, and who have so settled in New Zealand as aforesaid.”

In investigating the claims the Commissioner was to satisfy himself as to:

- the identity of the claimant

- his rank and good conduct from the service for the purpose of settling

- whether the claimant had previously obtained land or compensation in respect of his services or on retirement.

If the Commissioner was satisfied any claim had been substantiated he was to report to the Governor who was to submit all reports to Parliament at its next session. The Governor duly reported back to Parliament on the claims and to settle these Parliament passed the Naval and Military Settlers’ and Volunteers’ Land Act 1891. This Act authorised the Governor to:

“…grant to the several persons mentioned in the Schedule A to this Act certificates in the form or to the effect of the certificate in Schedule B, entitling them respectively to the remission of money in the purchase of land … in any part of the colony, as shall not exceed the sums specified in Schedule A , and set opposite the names of the aforesaid persons respectively.”

For the purpose of settling claims the Governor was to set aside in each land district lands to be surveyed in sections of suitable size and group into allotments for selection by holders of remission certificates. The holder of a certificate could select an allotment whose value didn’t exceed the value of his certificate. The certificates could only be used to purchase such set aside land.

Schedule A to the Act listed, by land district, approximately 570 individuals whose claims had been accepted. In the Land District of Westland there is listed:

Name: Mitchell,S.

Regiment or Corps: Royal Navy

Rank: B’tswain’s -mate

District: Westland

Amount Recommended: 30 pounds

The amounts recommended ranged from 15 pounds to 200 pounds and the remission certificates had to be exercised by 31 March 1894. It is uncertain what land Samuel used to purchase with his remission certificate.The 1891 Act also extended time for making claims under the 1889 Act from 31 December 1890 to 30 June 1892.

A further Naval and Military Settlers’ and Volunteers’ Land Act was passed in 1892 to reconcile differences between the approaches taken by commissioners in investigating claims and again extending time limits for making claims. This Act authorised the Colonial Treasurer to issue debentures for a money value instead of remission certificates. A Schedule listed further names entitled to debentures.

A Naval and Military Claims Settlement and Extinguishment Act was passed in 1896 with a view to a final settlement of these claims. The Act authorised the appointment of a Commissioner for the whole colony to inquire into outstanding claims. One such claim was from Samuel’s widow Agnes – Samuel having died in 1894. It seems that that Agnes considered the sum of 30 pounds awarded under the 1891 Act to be insufficient and she believed that because of his rank he should have been awarded 40 pounds. Accordingly she claimed for an additional sum of 10 pounds. This supplementary claim from her was referred to in a report to a Parliamentary committee by the Commissioner in 1898 but rejected. His remarks were: “Received remission certificate for service in 1892 but claims the amount is insufficient. Decision: not recommended.”

(d) Family Life

Samuel developed the farm he and Agnes had purchased near the Mikonui River, about 21 miles [35kms.] to the south of Hokitika. His Victoria Cross pension of 10 pounds was paid quarterly at the Post Office in Hokitika. Samuel and Agnes had 11 children being Ellen , Esther, Ada, Ruby, Isabella, Edith, Samuel, Stewart, John, William and Frank and their descendants now live in New Zealand and Canada.The Mitchells became very well known in the district and a local hill was named after Samuel and is still known as Mitchell’s Hill.

He drowned on Friday 16 March 1894 in the flooded Mikonui River near his farm at the age of 52.On the day of his death it appears he had tried to cross the Mikonui and had been struck by a floating tree or a fresh (a sudden rise in the river level) coming on very quickly and drowned. His body was found down the coast three days later by William Green a farmer in the area and a former sailor who had participated in the battle of Gate Pa.

Samuel’s funeral is said to have been one of the largest in the district up to that time. He is buried in the cemetery on a hill above the township of Ross .

Agnes was then left with 11 of a family to care for (the youngest being 2) and she had to cross the Mikonui river by horse or boat, there being no bridge. In the morning and afternoon she would tie the baby William to the leg of a table while she rowed the children across the Mikonui to and from school. Sometimes when the river rose the children would be unable to return from school and would have to stay with a neighbour. Agnes died in 1918 and is buried with Samuel in the cemetery at Ross, New Zealand.

The inscription on the tombstone reads:

“In loving memory of Samuel Mitchell V.C. who was drowned in the Mikonui River on 16th March 1894 aged 52 years. Also his beloved wife Agnes who died at Ross 23rd October 1918 aged 71 years. At rest. Erected by their family.”

RECOVERY OF THE VICTORIA CROSS.

In 1909 the following item appeared in the New Zealand press:

“SALE OF VICTORIA CROSS

At Messers. Glendinning’s Galleries a few days ago the Victoria Cross awarded to Samuel Mitchell, Captain of the Fore Top of His Majesty’s Ship ‘Harrier’ for conspicuous gallantry in New Zealand on the 29th April 1864, was sold for 50 pounds.”

Samuel’s wife, Agnes, contacted the Commissioner of Police in Wellington, New Zealand who advised that the Cross had been sold at the auction to a Colonel Frederick Gascoigne of Lotherton Hall, Aberford, Yorkshire, England. Col. Gascoigne was a collector of Victoria Crosses and other medals and the Cross had been obtained by Glendinnings from the executors of a collector in Bradford, England. The Colonel had a room, called “the Medal Room”, set aside at Lotherton Hall for his book and medals collection.

Between 1909 and 1925 Agnes, and on her death in 1918 her daughter, Edith, sought assistance to recover the Cross from the local Member of Parliament, the New Zealand Minister of Defence, the New Zealand Governor-General, the New Zealand High Commissioner in London (the equivalent of an ambassador), the Christchurch Returned Soldiers Association, the British Empire Service League in London and ,as Samuel had been a Mason ,the United Grand Lodge of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons of England.

Contact had also been made by the New Zealand Government with Colonel Gascoigne to recover the Cross and he stated he wanted another naval Cross to replace it and the sum of 70 pounds. In 1912 the Admiralty advised that a duplicate naval Cross could not be issued when the whereabouts of the original was known.

In 1927 the Duke of York (the future King George VI of Great Britain) visited Hokitika and the local Member of Parliament took up the matter with the Duke and explained the situation of the Cross to him. Upon his return to England the Duke caused enquiries to be made.

In June 1928 Edith wrote to Col. Gascoigne requesting he return the Cross. Col. Gascoigne replied that he had sold his medal collection to his son , Alvary, but he was sure his son would sell it to Samuel’s daughter for 70 pounds. Edith raised the sum of 70 pounds (it seems by way of a public fundraising campaign) and forwarded the money to the High Commissioner in London. In August 1928 the High Commissioner wrote to Edith enclosing the Cross and advising that the 70 pounds had been paid to the Gascoignes.

The Victoria Cross remained in Edith’s possession until her death when the Cross was gifted to the West Coast Historical Museum at Hokitika, New Zealand, in trust for all descendants of the time being of Samuel Mitchell. Col.Gascoigne died in 1937 and his medals collection was sold. In 1968 Lotherton Hall was gifted to the City of Leeds who now maintain it as a tourist site.

THE CANADIAN “VICTORIA CROSS”.

In November 1956 this report from Vancouver, Canada, appeared in newspapers in Australia and New Zealand:

“A 12 year old boy playing under a wharf here found what appears to be a genuine Victoria Cross issued in 1864 to a British Naval officer. Wayne Burton discovered the medal amid driftwood and sand as he hid from friends.The medal appears identical to those shown in official photographs of the Victoria Cross. The suspender from which the cross hangs is inscribed ‘S. Mitchell’ and the back of the cross is engraved with ‘April 29,1864.’

Records show that a Capt. Samuel Mitchell, Royal Navy, was awarded a Victoria Cross on that date. He won it while captain of the foretop on H.M.S. ‘Harrier’ during an attack in New Zealand waters. Captain Mitchell is not listed as a Canadian and there is no record of how the cross found its way to Canada.If the medal is genuine, it is probably one of the first issued. There have been 1,347 issued since it was first struck on order of Queen Victoria in 1856.”

At the time of this newspaper report Edith Mitchell had been corresponding with Captain P.J. Wyatt of HMS Harrier. Harrier at that time was a land based naval aircraft direction school on the cliff tops at Kete, near Haverfordwest in Pembrokeshire, Wales.

Edith sent Capt. Wyatt a copy of the newspaper report regarding the Canadian Victoria Cross together with photographs of the Cross she had recovered in 1928. In a letter of 18 October 1957 Capt. Wyatt wrote to Edith:

“I took the photographs, together with those of the one found in Vancouver, to a Mr. Dawes, of the firm of Hancocks, in London, who is probably the most knowledgeable man on the subject alive today. That firm have had the monopoly of casting Victoria Crosses since they were first inaugurated. He stated with more decision than I expected from such wary people that yours was the true one, and that found in Vancouver a certain counterfeit.We speculated on the reason why anyone would make such a copy; it appears that this was quite a popular habit in the past. A man in Canada called Mitchell, who had probably been a sailor, and wanting to appear as a hero or get employment, found that a namesake had actually got a Victoria Cross. For a very small price a blank copy of the cross could be procured, the name stamped on, and a hero was born! From the look of it, the Vancouver one had been worn a lot, and must have appeared in many a veterans parade.”

Late in 1999 I found that a private medal collector in Auckland has this Victoria Cross that was found in Canada. Apparently after it was discovered it had been sold to an American collector and from the United states had found its way to London. The Auckland collector purchased the medals in London about 4 years ago and now has them on display in his home.