This battle was fought on 29 April 1864 and was one of a number of engagements fought in the period 1860 – 1872 in what are known as the New Zealand Wars or the Māori Wars. These wars were fought between the native Māori and the British Government which at that time administered New Zealand as a colony. Gate Pa was to be a major defeat for the British at the hands of an out numbered Māori and even today there is no clear reason why this defeat occurred.

Before 1864 the battles had been fought primarily in the Waikato and Taranaki regions which are in the central and western parts respectively of the North Island of New Zealand. By 1864 missionaries had established a mission station called Te Papa on a peninsula near the present day city of Tauranga in the eastern part of the North Island. The harbour of Tauranga in 1864 was the only port open to Māori to supply the Waikato region and the area around the battle site was itself a source of supply for them. Also there were rumours that 1400-1500 Māori from the far eastern side of the North Island were going to pass through the Tauranga area to join the Waikato Māori.

The Governor of New Zealand , Sir George Grey, decided to send a force to to the Tauranga area to blockade any reinforcements and supplies reaching the Waikato Māori and in January 1864 the British build up based at Te Papa mission station commenced.

The local Ngatirangi tribe led by Rawiri Puhirake had been supporters of the Waikato tribes fighting the British and the Ngatirangi now gathered in the Te Papa area to fight the British.

In March 1864 Rawiri issued a challenge to the British to fight. In the challenge,which was written by Henare Taratoa who had been educated by the Church Missionary Society, the word “Pakeha” is a Māori word for a non-Māori , commonly used to refer to a European, and is in common usage today.

March 28, 1864

Potiriwhi, District of Tauranga.To the Colonel,

Friend, -Salutations to you. The end of that. Friend, do you give heed to our laws for regulating the fight.

Rule 1. If wounded or captured whole, and butt of the musket or hilt of the sword be turned to me, he will be saved.

Rule 2. If any Pakeha, being a soldier by name, shall be travelling unarmed and meets me, he will be captured, and handed over to the direction of the law.

Rule 3. The soldier who flees, being carried away by his fears, and goes to the house of the priest with his gun (even though carrying arms) will be saved. I will not go there.

Rule 4. The unarmed Pakehas, women and children, will be spared.The end. These are binding laws for Tauranga.

By Terea Puimanuka

Wi Kotiro

Pine Amopu

Kereti

Pateriki.Or rather by all the Catholics at Tauranga

The British didn’t know what to make of this document and ignored the challenge and the rules.

At the beginning of April 1864 Ngatirangi started to build a pa (a Māori fortified position) at a place called Pukehinahina and which was about 3 miles [4.8km.] from the Te Papa mission.

The Māori word “Pa” generally denoted a fortified place built and used by the Māoris of New Zealand. Such places included a fortified village and a fortified place of refuge.

Pas were numerous in pre-European times and were often found on hilltops, ridges, cliffs, islands and headlands.

With the arrival of the European and the musket (c.1815) the design of a pa underwent a significant change to reflect the longer range of a musket and the use of cannon. The Māori began to introduce typical European features such as rifle-pits, ramparts and bastions.

By the time of the Battle of Gate Pa in 1864 Pa design had reached a high point and Gate Pa had most of the features of the new style pa. Those features were:

1. Pekerangi (Light Fence)

The pekerangi was a light fence which usually surrounded the pa. It was about 3-4 feet high and the bottom of the fence about 12-18 inches above the ground. This was so the Māori could fire muskets underneath the fence at an advancing opposing force.

The pekerangi was also intended to deaden shot and cannon ball and to delay a storming party.

2. The Trench

Behind the pekerangi was a trench about 4 feet deep where Māori could fire at an advancing force and then duck down to reload their muskets.

3. The parapet

Behind the trench was a parapet about 6 feet high formed out of the earth thrown out of the digging of the trench.

4. The Underground Chamber

Within the parapet the Māori would excavate a number of underground chambers to serve as shelter from muskets and cannon balls. These chambers would be covered with low pitched rooves made of earth and and logs of timber. A witness to these chambers in a pa in 1860 said:

“The pa consisted of ten chambers excavated in the clay, communicating with each other, three at each side, and two at each flank, each calculated to contain from twenty to twenty-five men. These chambers were wider at top than at bottom, sloping from the centre to give strength and width of base to the work. The chambers were overlaid with rafters and a layer of fern and earth between two and three feet deep, the whole surrounded with a double fence, filled up with fern and earth, communicated with the interior, and from whence the inmates could fire without in the least exposing themselves.”

5. Interior Design

The interior design of the trenches was like a labyrinth and designed to confuse an attacking force. Often there would be connecting tunnels within the trench system so that the defenders could move within the pa sheltered by the earthworks.

Of this feature Major -General Sir J.E. Alexander says in his book “Bush Fighting; Incidents of the Māori War in New Zealand” regarding the defeat at Gate Pa:

“The repulse, without doubt, arose from the confusion occasioned by the intricate nature of the interior, honeycombed with rifle pits and under ground passages, and the enemy lying down had, no doubt, considerable advantage in shooting at our men from concealed positions.”

All of these features were present at Gate Pa as can be seen on the a plan of that Pa. There were some 8 underground chambers.

The site of Gate Pa was located on a ridge approximately 300 yards [274mts.] across and was sited where a deep ditch had been dug and there was a boundary fence between Māori and European land. This fence had a gate in it to allow bullocks and carts to pass and so to Europeans the pa came to be known as the Gate Pa.

The main redoubt of the Gate Pa stretched about 87 yards [80 mts.] along a rise with a smaller redoubt some 22 yards [20 mts.] from the main redoubt. The pa was situated on a spit of land between a swamp on one side and a river on the other. The main redoubt (where the Naval Brigade was to attack) was some 22 yards [18 mts.] in depth. It consisted of parapets, rifle pits and a triple line of trenches covered with timbers through which the Māori could fire. There were also covered dugouts and underground shelters.The main redoubt was enclosed by a light palisade fence.

The main redoubt contained about 200 Māori and the smaller redoubt 40. The smaller redoubt consisted of a double line of covered trenches also surrounded by a palisade fence. Between the 2 redoubts was a simple ditch which was to be occupied by 600 Waikato Māori who never arrived.

On 21 April 1864 General Sir Duncan Cameron arrived in HMS Esk with his staff and on 26 April 600 sailors and Royal Marines were disembarked from HMS Harrier, Curacoa, Esk and Miranda. One 110-pounder Armstrong gun and two 40-pounder Armstrong guns, along with 14 smaller artillery pieces, were unloaded from HMS Esk and taken to within firing distance of the Gate Pa.

So by 28 April 1864 the British had assembled 1,300 soldiers primarily from the 43rd and 68th Regiments under General Sir Duncan Cameron.The 43rd (Monmouthshire) Light Infantry Regiment (‘Wolfes’ Own’) commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel H.J. Booth had sailed from Calcutta, India, in 1863 and while in New Zealand served in the Waikato, at Gate Pa, Te Ranga and later in Taranaki. It returned to England in 1866 after 15 years of overseas service. The 68th (Durham) Light Infantry Regiment (‘The Faithful Durhams’) commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel H.H. Greer had come from Burma in 1864. It took part in Gate Pa, Te Ranga and was in Wanganui. It returned to England in 1866.

A Naval Brigade of 429 officers and men from a flotilla of Australia Squadron ships including HMS Curacoa, Esk, Falcon, Harrier and Miranda had also been assembled under Commodore Sir William Wiseman .

General Cameron had fought in the Crimean War (1854-56) against Russia and had led the 40th Regiment at the Battle of the Alma and the Highland Brigade at Balaclava and the siege of Sebastopol. He first came to New Zealand in 1862 to take charge of the 2nd Taranaki Campaign, and before the Tauranga Campaign where the Battle of Gate Pa was to occur had commanded throughout the Waikato War of 1863-64.

General Cameron intended to use artillery to make a breach in the main redoubt of the pa and then assault the breach with his soldiers and the Naval Brigade. To prevent the Māori escaping from the pa at 9pm on the night of 28/29 April he sent the 68th Regiment under Lieutenant Colonel Greer around the mudflats which emerged at low tide at the side of the pa to hold the land at the rear intending to cut off any retreat for the Māori from the pa..

At daybreak on the morning of Friday, 29th of April 1864, in a drizzling rain, the bombardment of the pa commenced. The artillery included 8 mortars (the 2 heaviest throwing a 46-pound shell), 2 howitzers (throwing a 24-pound shell), 2 naval cannon (throwing the standard 32-pound shell) and 5 Armstrong guns. The Armstrong guns comprised one 110-pounder, 2 40-pounders, and 2 6-pounders. In his book “The New Zealand Wars” James Belich says (at p.182) in referring to the mortars, howitzers and cannon:

“Powerful as they were, these weapons were conventional, single-cast and muzzle-loading, but the British were also equipped with the latest science could provide: the Armstrong gun. This gun was both rifled and breech-loading, and a new process was used to cast it which made possible the use of a huge weight of shell without a corresponding increase in the weight of the gun. Invented in 1854, the Armstrong had first been used at the attack on the Taku forts in China in 1860. These were tremendously strong masonry fortifications of the conventional type and the Armstrongs used were only twelve-pounders. Nevertheless … their shells succeeded in ‘actually knocking the wall about.’ At Gate Pa, apart from two six-pounder Armstrongs, there were two 40-pounders and one enormous 110-pounder – ‘probably the heaviest gun ever used on shore against tribesmen’. It is scarcely surprising that the naval crew of this early Big Bertha maintained that they were ‘going to blow the Pah to the devil’.The concentration of British artillery was of considerable power even in absolute terms. When it is considered that these guns fired unhampered by enemy artillery from a distance of 350 to 800 yards [320 to 730 meters] at a target of less that 3,000 square yards [2,500 square meters], their power appears awesome. Gate Pa was the ultimate test of strength between British and Māori military technologies, between modern artillery and the modern pa. In a wider sense, it was to be the first of many contests between breech-loading, rifled, composite-cast heavy artillery and trench-and-bunker earthworks.”

Belich observes that in proportion to the size of the pa and its garrison, the artillery bombardment was comparable to those in the First World War.

The bombardment continued until midday. During this bombardment the Māori leader, Rawiri, strode up and down the parapets calling out to the gunners at each shot: “Tena tena e mahi i to mahi” (go on with your work, do your worst).

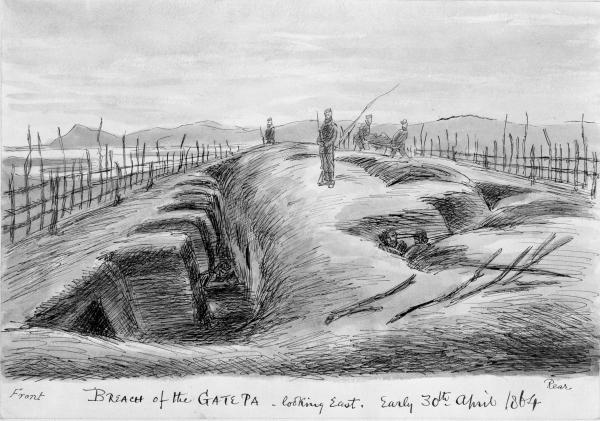

A 6-pounder field piece had been taken to an adjoining higher ridge and commenced firing on the smaller redoubt. All the other guns then recommenced firing until 3pm.The artillery bombardment was said to be the heaviest of the Wars. By this time a breach had been created on the right hand corner of the main redoubt and with the rain and the bombardment the defences were very muddy.

A 300 strong assault column had been formed comprising 150 men from the 43rd Regiment under Colonel Booth and the same number from the Naval Brigade (including Samuel) under Commander Hay (then aged 28). Another group of 300 men again split between the 43rd and the Naval Brigade comprised the reserve with orders to follow the assault column into the pa.

At 4pm on 28 April the assault began when the signal, a rocket, was fired. The assault party 4 abreast (2 soldiers, 2 sailors), with their officers at each side of the column, rushed toward the breach in the main redoubt. Covering fire was given by the remaining soldiers of the 43rd and by the 68th soldiers in the rear.

In a few minutes the assault column was through the breach and inside the pa. As the assault column came into the pa it is said Māori attempted to escape at the rear of the pa. However because of the presence of the soldiers of the 68th, who were advancing towards the rear of the pa, they were unable to escape and turned around and came back into the pa. The Māori then sought shelter in the covered dugouts and underground shelters in the pa and commenced firing on the soldiers and sailors within the pa and Māori from the smaller redoubt joined in the firing. The Māori also engaged in hand-to-hand combat within the twists and turns of the pa.

General Cameron, believing the pa had been taken, ordered the reserve assault force to enter the pa and these men only added to the confusion of a large number of men crowded into a small space.By now it was getting onto dusk and many of the British officers (including Colonel Booth and Commander Hay) had fallen.The next few minutes decided the day.

For an unknown reason a panic ensued amongst the British forces. It is said a subaltern called out “My God, here they come in thousands!” and this may have been because Māori were returning to the pa. Others say the order “Retire” was given.

The disorganised British now broke and retreated from the pa and fled back to their own lines with the Māori from the main redoubt in pursuit. At the same time the Māori in the smaller redoubt kept up a crossfire on the retreating soldiers and sailors.

As Commander Hay’s coxswain, Samuel had accompanied Commander Hay in the initial assault and when Hay fell wounded he ordered Samuel to leave him and go to safety. Samuel refused to leave him although repeatedly ordered to do so and carried Hay, amid a fusillade of Māori bullets, to the British lines.As Samuel was carrying Hay he was met by Staff Surgeon William Manley who, notwithstanding the chaos around him, dressed Commander Hay’s wounds under fire and then went to attend to other wounded in the pa. It’s said he was one of the last officers to leave the pa and Staff Surgeon Manley also received a Victoria Cross for his actions on this day.

General Cameron rallied his men about 100 yards from the pa and they threw up earthworks. Given it was dusk General Cameron decided against another assault. British dead and dying remained in the pa during the night and a Māori, before leaving the pa, gave water to a number of soldiers, including the dying Colonel Booth of the 43rd Regiment. At 5am the next morning a sailor from Harrier crept up to the pa and found the Māori had left during the night slipping past the men of the 68th.Commander Hay died the next day and his dying wish was that Samuel be recommended for the Victoria Cross and this recommendation was taken up by Commodore Wiseman.

British casualties were more than a third of the assault force with 100 men killed or wounded. Ten officers were killed while 28 non-commissioned officers and privates were killed and 73 wounded. The 43rd Regiment lost 20 killed (including its colonel, Colonel Booth, 4 captains and a lieutenant) and 12 wounded. The 68th Regiment lost 4 killed and 16 wounded. The Naval Brigade lost 13 killed (including virtually all of its officers) and 26 wounded. Total Māori losses were estimated at 25.

There was a great outcry, both in New Zealand and England, that a force of some 1,700 soldiers and sailors could have been defeated by 200 Māori and General Cameron was roundly criticised. To contemporaries Gate Pa seemed a defeat ‘perhaps unparalled in British military annals.’ In blaming Cameron four factors were highlighted as contributing to the defeat:

- leaving the assault so late on a rainy day so that dusk came on during the fighting;

- using a mixed force of soldiers and sailors for the assault;

- not assaulting the smaller redoubt at the same time as the larger redoubt. This would have avoided the Māori concentrating their fire and weight at one point;

- the quick advance of the reserve assault force which added to the confusion in the pa.

Another school attributed the defeat to an accident and the official explanations reflected this view. These accounts referred to the complicated nature of the defences and the loss of officers. Most contemporary historians take the view that the retreating Māori driven back by the 68th Regiment induced the panic.

The historian James Belich makes the argument that the Māori deliberately created a trap for the British. That in fact the Māori garrison did not evacuate the pa but concealed themselves in underground chambers covered with tree branches and earth. Then when the British assault party entered the main redoubt the Māori commenced firing at close range and the assault force could not effectively retaliate. This continued for perhaps 5 minutes and then the British broke. He states in his book the New Zealand Wars:

“For one thing, the trap into which the British assault party fell was surely a remarkable tactical ploy. The use of concealed or deceptively weak-looking fortifications to ambush attackers was … a major element of the tactical repertoire made possible by the flexible modern pa. Rawiri’s trap at Gate Pa was perhaps the ultimate refinement of this technique. It amounted to using the enemy’s overwhelming strength against him and it involved the fearsome risk of allowing the assault-party, which alone outnumbered the garrison, into the main redoubt. Inside, the redoubt was less a fortification than a killing ground, as soldiers who inspected the redoubt after the battle attested. ‘Those who were in this morning for the first time say that they never saw such a place in their life, and that you might as well drive a lot of men into a sheep pen and shoot them down as let them assault a place like that.'”

Also the Admiralty, while conceding that the Navy could not have stood by in the Waikato and Tauranga campaigns was not pleased with its losses at Gate Pa and reminded Commodore Wiseman of”..the serious inconvenience which may arise from having HM ships rendered inefficient by the loss of so many of their best officers and men.” Thereafter, except in urgent situations, Wiseman was not to detach men to take part in land battles and limit his aid to matters such as water transport, provisions of stores and landing and manning of artillery.

It was not until almost 2 months later, on 21 June 1864, that the British had an opportunity to avenge their defeat at Gate Pa.

On that day Colonel Greer, with some 600 men of the 43rd and 68th Regiments,came across about 500 Ngatirangi, led by their chief Rawiri, fortifying a position at Te Ranga about 4 miles (6.5km) inland from Gate Pa. Greer opened fire and sent for reinforcements from Te Papa. When these arrived, about 200 men and an Armstrong gun, the British charged. Unlike Gate Pa they charged across the whole of the Māori line. After an initial volley the fighting was almost all hand -to-hand and very bloody. The Māori were slowly being forced from their lines when Rawiri was killed and they then retreated. This battle was to see Victoria Crosses awarded to Captain Frederick Smith and to Sergeant John Murray. Also killed at Te Ranga was Henare Taratoa who had written the rules for battle given to the British at Gate Pa and who had fought at Gate Pa. A copy of the rules was found on his body.

The defeat at Te Ranga broke the resistance of the Ngatirangi and in July 1864 they came into Te Papa to surrender their weapons and pledge peace to Governor Grey.

The body of Rawiri Purihake, who had been buried at Te Ranga, was later re-interred at the cemetery at Tauranga next to his opponent of Gate Pa, Colonel Booth.

An interesting sideline is that during the night of 29-30 April 1864, while the wounded lay in the Pa, a Māori risked his life to bring water through the English sentries to the English wounded.. It’s said the Māori was Henare Taratoa who had been educated by Bishop Selwyn from 1845 to 1853. When war broke out Henare returned to his tribe and fought at Gate Pa. He was subsequently killed at Te Ranga in July 1864.

At the end of the New Zealand Wars Bishop Selwyn’s services were recognised by a medal and a public subscription was raised and given to him. After the War Bishop Selwyn returned to England and went to Lichfield Cathedral in 1867. He built an Episcopal Chapel opposite to the north side of the Cathedral. With the money he obtained in New Zealand he had painted windows placed in his chapel and each window represented the chivalrous side of a soldier’s life. One window represents David pouring out water which 3 soldiers had fetched from the well of Bethlehem at the risk of their lives. This was intended to record Henare’s chivalrous act.

Today little remains of the Pa itself and on the site of the main redoubt of Gate Pa there is the small Memorial Church of St. George which was built in 1900. The remaining area of the pa has been developed for housing and is now a suburb of Tauranga called Greerton after Colonel Greer. One of the residential streets near the church is called Mitchell Road after Samuel and the main road going past the church is called Cameron Road after General Cameron. Near the city centre of Tauranga is the original mission house and graveyard of Te Papa where Māori and Europeans who died at the battle are buried. The New Zealand city of Hamilton was named after Captain Fane Charles Hamilton, the commander of HMS Esk, who was killed in the battle of Gate Pa.

For a video made by Radio New Zealand in 2024 please see this link: